Introduction — A History of Pitching Stats

Here is where Sabermetrics gets controversial: pitching stats. How to measure a pitcher’s impact on the game is something which is incredibly difficult. A hitter has a very isolated impact—they are the one who hits the ball and no one else on their team assists in that—which makes a hitter’s impact on their team’s run scoring quite easy to measure. However, this same clear delineation does not exist with pitchers. A pitcher is told which pitch to throw by the catcher, then the pitcher throws that pitch, which results in the batter hitting the ball (which the batter has some degree of control over obviously), and then fielders on the pitcher’s team field the ball. Isolating just the pitcher’s impact on the game is something which is incredibly difficult.

For decades, a pitcher’s W/L (win-loss) record was seen as the holy grail of pitching stats, and the stat by which many members of the BBWAA based their Cy Young votes on. If a pitcher’s team is winning often, they must be doing an amazing job. However, this has a couple of problems. First, it ignores the impact of the batters of a team. If a pitcher is stuck on a team that can’t hit, why should they be seen as worse? Poor Jacob deGrom. But secondly, it is a comparison which has become even less valid over the years. 120 years ago, pitchers would pitch complete games regularly, being more a norm than an exception. But nowadays, pitchers normally only go 5 or 6 innings unless they are having an exceptional outing. Teams now have relief pitcher corps to take the last few innings of a game and maximize run prevention. So a starting pitcher’s W/L record is less valid to evaluate a pitcher than ever.

As a result of this increase in prevalence of relief pitchers, a baseball statistic invented by Henry Chadwick caught steam in the 20th century: ERA (Earned Run Average). It is calculated by taking the number of earned runs (I have so many gripes about earned runs that I will be saving for some other article, because it would be too long of a tangent), dividing it by the number of innings a pitcher pitches, and multiplying it by 9, to get the number of earned runs a pitcher allows on average per 9 innings. This stat improves on W/L records by no longer penalizing a pitcher for having a poor offense or a poor relief pitcher who allows a lot of runs. However (and this is where my opinion gets controversial among many baseball fans), I do not think it captures the essence of pitching.

What is the goal of a pitcher?

Many people will say that the goal of a pitcher is simple: to prevent runs. Of course, that has not always been the case—the goal of a pitcher used to be to win games before it was to prevent runs from scoring. But now the mainstream opinion is that pitchers should be preventing runs. But I personally say that is wrong.

I personally believe that the goal of a pitcher is to make it easier for their team to prevent runs. That distinction may sound meaningless, but it is quite large. The goal of a team is to prevent runs from scoring. However, a team consists of many people who are not pitchers and who play defense. This defense is a large impact on the number of runs a team allows. As a result, the job of a pitcher should be to make it easy for the defense of their team to prevent runs. If a pitcher allows hard line drives but their team somehow catches them, why should the pitcher be rewarded? Or if a pitcher allows hard fly balls to the warning track that could be home runs with just a tiny gust of wind, why should they be rewarded? The way to measure how well a pitcher has done this is varied and controversial, but one such way is through using FIP, Fielding Independent Pitching.

FIP

FIP has a formula which is simple in many ways and utterly confounding in others.

FIP Formula

There are a few things in FIP’s formula to be explained.

- What is the FIP constant?

- Where are the singles and doubles and triples?

- Where do those strange numbers come from?

Starting off with the first and most simple question: what the FIP constant is. FIP is designed to be on the same scale as ERA. That means that FIP must be scaled so that the league’s cumulative FIP is equal to the league’s cumulative ERA. So, the FIP constant follows this formula:

The league’s FIP is calculated simply by putting the total HR, BB, HBP, K, and IP in the league into the FIP formula and you get the FIP constant (also found on Fangraphs’ Guts page) which is usually somewhere around 3–3.2.

Next, why doesn’t FIP include the number of outs a pitcher gets or the number of singles or doubles or triples a pitcher allows? Because it is supposed to be Fielding Independent Pitching. The goal of this statistic is to attempt to isolate a pitcher’s individual contributions to their team’s success and so, in order to do this, it makes a controversial assumption: all balls in play have equal value to the pitcher. It essentially assumes that all balls in play are essentially random in terms of the pitcher’s control over it—if they allow a double or a flyout is not in the pitcher’s control. So, it excludes them from the formula (in a way which will be explained later when explaining the constants in the FIP formula). This is incredibly controversial and a bit dubious. Just intuitively, pitchers must have some level of control over batted ball outcomes. However, at the time FIP was created, there was no good way to isolate the factors behind batted ball outcomes, and so they decided to go with an extreme approximation. If you think about it, this is no more absurd than the assumption behind ERA that pitchers have full control over batted ball outcomes.

Finally, an explanation of the weights in FIP. This is another strange aspect of FIP in that the numbers have been calculated just once (many years ago) and have not been adjusted since. However, the numbers used in the FIP formula are kept as integers for simplicity (perhaps a simplicity which is no longer necessary) and are incredibly close to the mathematically “correct” numbers. They are calculated from linear weights, specifically, run-scoring scaled linear weights (as opposed to the ones used in the wOBA formula, which must be divided by the wOBAscale to be scaled to run scoring).

First, let’s look at all the relevant weights (for the year 2024 as calculated by me):

HR — 1.399 BB — 0.323 SO — -0.269 BIP — -0.0267

BIP is a new linear weight. BIP stands for ball in play and represents the average value of all balls put into the field of play (a home run does not count as a ball in play). These weights above are scaled so 0 is the average plate appearance, so they are scaled as runs above average. From these values, we can formulate a simple formula for FIP where 0 is average: (I may be wrong here, but I believe this formula should be in essence equivalent to wRAA, though it does assume no agency over BIP outcomes so it won’t exactly match)

Next, we can add 0.116 (the league R/PA) to each weight to get the total runs allowed by a pitcher:

We can also recognize that BIP are simply all the PA in which a pitcher does not have a HR, BB, HBP, or SO to rewrite the BIP term:

We can expand the brackets into 4 terms (PA, HR, BB + HBP, and SO) and find their like terms in order to adjust the weights:

You can then divide each term by IP and multiply by 9 to get runs per 9 innings:

We are very close to FIP! We can see the finish line! First, I’ll clean up the formula:

Next, we need to change the scale of this formula. Currently, it is scaled to output something in terms of total runs a pitcher is expected to allow based on these stats. However, we want it to be on the same scale as ERA, so we need to multiply the whole equation by the ratio of earned runs to total runs in the league. For 2024, this is about .916. This gives us an equation for FIP!

The last term can be replaced with the FIP constant term to adjust FIP’s average to be the same as ERA’s average. As you’ll see here, the weights are close to the original weights for FIP, just rounded. The weight for a home run is, however, too high in the FIP formula. But in the grand scheme of things, that is not a major issue. And, at the time FIP was created, it is likely that the HR weight was closer to being correct.

Why do we replace the PA term be replaced with the FIP constant?

The answer here is complicated and not super clear to me. The PA term could be based on the number of plate appearances a pitcher individually has. However, it requires a more precise version of the FIP weights to be used. When FIP was created, its weights were left rounded to the nearest integer for simplicity’s sake. That may not still be necessary, but it is just how FIP works.

Additionally, I have found that using the above formula for FIP with PA/IP*0.7358 results in an underestimate of ERA. For 2023, the league FIP using this formula is 4.09 while the league ERA was 4.33 as a whole. So this is a bit of a problem when the goal for FIP is to be used as a stat that exists on the same scale as ERA. I’m, again, not quite sure why this is. I don’t see why this method of deriving the formula underestimates FIP, but it does. It could be an issue with my linear weights, but I doubt that, because they are broadly in line with other linear weights, and I see no issues with my program.

Regardless of how you deal with the PA/IP term, that term is likely to be almost constant for a given pitcher (or fully constant for the whole league if you use the normal method of constructing FIP), which means that the value of a BIP is simply defined by that term. If a pitcher only allowed balls in play—no strikeouts, no home runs, no walks—their FIP would equal the FIP constant, and thus their ERA would be expected to also equal the FIP constant.

Analyzing FIP

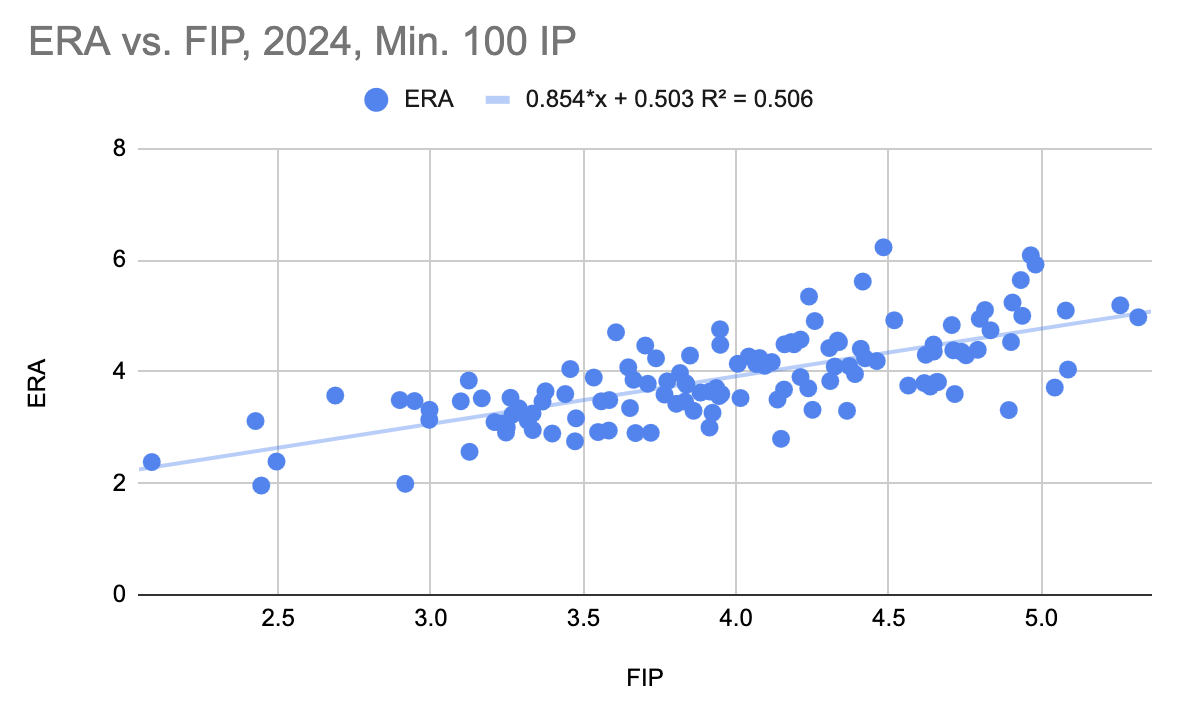

Figure 1. ERA vs FIP, 2024, Minimum 100 IP

Figure 1. ERA vs FIP, 2024, Minimum 100 IP

Figure 1 shows every pitcher in 2024 who had at least 100 IP, their FIP on the x-axis, and their ERA on the y-axis. As you can see, a decent correlation between the two. However, the goal of FIP is not to tell you a pitcher’s ERA, but instead to try to be a more accurate descriptor of a pitcher’s contribution to the team. How can we determine if it has achieved that goal? Recall that if one stat is better at measuring a player’s talent (i.e. their true, isolated contribution to a team, free of random noise and the contribution of other players) than another, then it should also correlate to a greater extent with their future results than that other stat. So, what we can do is we can see how well FIP predicts the future vs ERA predicting the future. Spoiler alert, FIP will do better than ERA. I am telling you that beforehand because what a lot of people assume when people mention this is that it means that FIP is intended to be a predictive stat—it isn’t—and I want to clarify the meaning of that result. FIP is simply meant to be a stat which is more descriptive of a pitcher’s individual contribution to their team, and a sign that it has succeeded at that goal is its predictive nature.

Anyways, there are two ways to determine that FIP is more predictive than ERA: its correlation with future ERA and its self-correlation. Starting with its correlation with future ERA. Taking data from 2023 as the “current” year and data from 2024 as the future year, 2023 ERA correlates with 2024 ERA with a correlation coefficient of 0.057, quite low. However, 2023 FIP correlates with 2024 ERA with a correlation coefficient of 0.135. Not super high, but significantly higher. Where FIP really shines, though, is with its self-correlation—if FIP reflects a pitcher’s true talent, you would expect it to be similar from year-to-year—where it has a correlation coefficient of 0.272 compared to ERA’s self-correlation coefficient of 0.057. So, FIP is clearly much more predictive than ERA, which is indicative of its better reflection of a pitcher’s individual contribution and true talent.